Roma Women, Land, & Environmental Injustice: Reclaiming Agency in Toxic Landscapes

This blog post was contributed by PLUS Change Ambassador Marina Csikos and is part of our series featuring personal accounts from our Ambassadors. These blogs offer first-hand reflections on the challenges and opportunities shaping land use planning across Europe and beyond.

Ambassadors contribute to PLUS Change discussions on equitable land use, representing the interests of groups that may be excluded from or underrepresented in land use planning and decision-making in Europe. These individuals bring valuable perspectives rooted in their experiences and lived realities, helping to shed light on how land use change impacts different communities.

Roma women, who make up nearly half of Europe’s 10–12 million Roma population, experience some of the most severe forms of structural exclusion across the continent. According to the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, over 60% of Roma households lack access to essential sanitation services, and fewer than 20% of Roma women are in formal employment in several EU member states. Romani women face disproportionately high rates of poverty, poor health, and educational exclusion. These gendered inequalities are exacerbated by environmental racism; Roma women are especially vulnerable to pollution, inadequate infrastructure, and energy poverty—yet remain central to sustaining their communities and leading local resistance efforts.

The intersections of gender, race, and class are vividly illustrated in the environmental degradation disproportionately endured by Romani communities across Europe. Among the most structurally impacted are Romani women—positioned at the nexus of systemic discrimination, spatial segregation, and environmental harm. The recent issue of Critical Romani Studies (Vol. 7, No. 1, 2024) illuminates these dynamics through analyses rooted in political ecology, historical exclusion, and the lived experiences of marginalised communities.

In Turkey’s Ergene River Basin, Romani populations—many of them descendants of forcibly resettled Romani-Muslim migrants from Greece—have been relegated to the frontlines of environmental collapse. Sergen Gül’s contribution to the issue details how neoliberal industrialisation and state-sanctioned economic modernisation have generated zones of sacrifice where Roma are rendered both hyper-visible and politically invisible. Factories, lacking adequate waste treatment infrastructure, discharge toxic pollutants into the Ergene River, transforming what was once a site of agricultural vitality into a space of death and contamination.

Romani women, as primary caregivers and managers of domestic environments, face disproportionate exposure to the compounded effects of environmental racism. Reliance on coal and wood for heating and cooking leads to persistent indoor air pollution—elevating the risks of respiratory disease, especially among women and children. These harms are further entrenched by spatialised neglect: communities situated on degraded lands, near industrial zones, or in flood-prone areas are systematically denied access to clean drinking water, sanitation infrastructure, and waste removal services. As the foreword to the journal notes, such exclusion is not incidental but foundational—emerging from historical logics of extractivism, white supremacy, and capitalist accumulation.

Environmental injustice, as conceptualised within the issue, must be understood not solely as the unequal distribution of environmental harms, but also as the denial of recognition and participatory parity. Romani women inhabit multiple marginalised subject positions within a system that simultaneously commodifies their labour, dispossesses their communities, and pathologises their identities. The symbolic association of Roma with waste, pollution, and disorder reinforces a racialised ecological citizenship where Roma are cast as threats to the environment rather than as its defenders.

Yet, Romani women are not passive victims. The narratives documented in the issue illustrate forms of embodied resistance, knowledge production, and claims to justice that unsettle dominant environmental governance paradigms. In North Macedonia, Romani women recyclers—often excluded from formal waste economies—play a central role in circular environmental practices, even as they risk their health daily. In Edirne, Turkey, women’s memories of an unpolluted Ergene River become tools of political consciousness, used to critique industrial expansion and state neglect. In Cluj-Napoca’s Pata Rât settlement, Romani women actively participate in community-based monitoring of air quality and mobilise for housing rights in the face of state-imposed segregation. These practices, though often informal and unrecognised, constitute critical interventions that challenge racialised and gendered hierarchies of environmental governance.

The European Union’s recent incorporation of environmental justice into the Roma Strategic Framework marks a critical policy opening. However, without centering the voices and epistemologies of those most affected—particularly Romani women—such frameworks risk reproducing the very exclusions they purport to address. True environmental justice demands more than technocratic inclusion: it necessitates a radical rethinking of whose lives and landscapes are rendered disposable, and whose knowledge is deemed actionable.

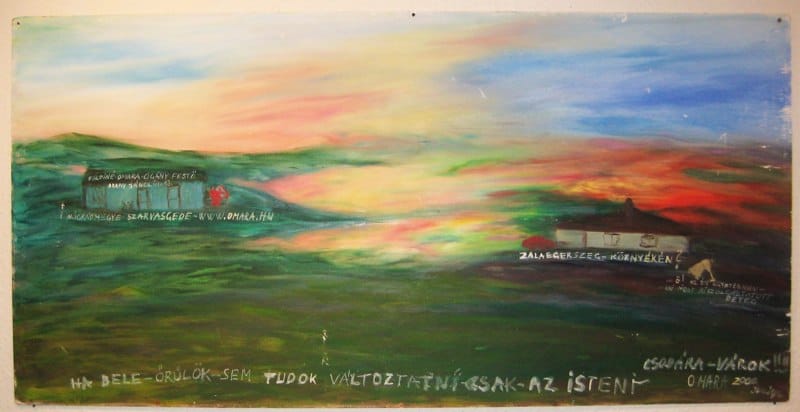

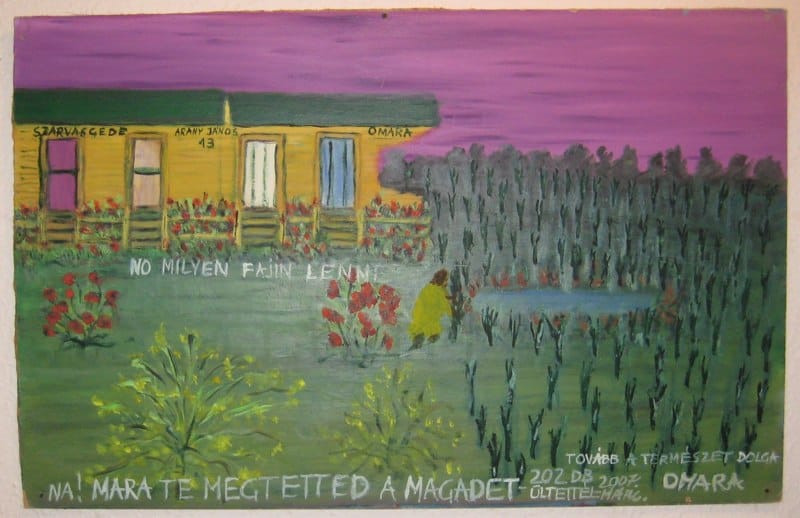

Banner painting by Olah Mara Omara, available at http://www.omara.hu/kepek.html#60.