PLUS Change In Depth: Spotlighting the role of System Maps in land use change research

Written by Edvin Andreasson of KE.

Navigating land use strategies is complex considering the natural, social, economic, and political nature of the current problems at hand. The issues are further compounded by the involvement of multiple stakeholders, each bringing diverse perspectives and objectives. Additionally, aligning these strategies with local, national, and EU regulations adds another layer of intricacy to the process.

Addressing such complexity necessitates a comprehensive and holistic approach, fostering a deeper understanding of the current situation, the historical drivers of land use changes, and potential pathways for future development. Systems thinking is a methodology that provides tools founded in co-creation and multi-stakeholder engagement for a “whole system” analysis. By applying systems thinking to the analysis of land use dynamics, it is possible to integrate social, economic, environmental, and political drivers of change to create a shared understanding amongst stakeholders. In the Plus Change project, this is achieved through the creation of Systems Maps, also called Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs).

Key components of system maps

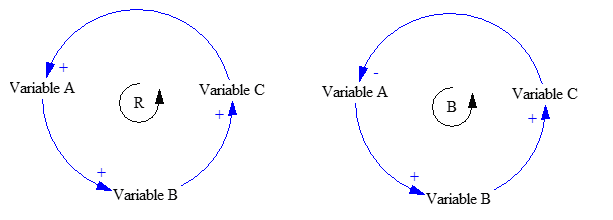

System maps detail the connection between variables in a system, using arrows that denote the influence one has on the other. For example, if an increase in Variable A leads to an increase in Variable B, this indicates a direct causality that is represented with the sign “+”. The use of a “-” sign, on the other hand, implies that a change in variable A would result in an opposite change in variable B. If these variables link together to form a circle, that circle represents a feedback loop. If an initial increase in A leads to a further increase in A after completing the loop, this signifies a self-reinforcing feedback loop (R). Conversely, if an increase in A results in an eventual decrease after following the loop, this is called a balancing feedback loop (B).

Figure 1. Loops

Leveraging Systems Thinking for Sustainable Land Use Strategies

To achieve this, PLUS Change focuses on developing strategies to assist decision-makers in addressing the complexities of land use, utilising systems thinking and systems maps as valuable tools for the project. By capturing historical drivers to understand “how we got here,” the systems map supports a systemic analysis of their possible evolution into the future. Some historical drivers of change may gain in strength, others may diminish in relevance, while new drivers may emerge.

This exercise was carried out for the EU, using statistics and policy analysis across all European countries, as well as for the Practice Cases. A connection exists across these assessments: when common patterns emerge in local cases, it suggests that similar dynamics may be present at the EU level, providing valuable insights for evaluating current EU policymaking on sustainable land use.

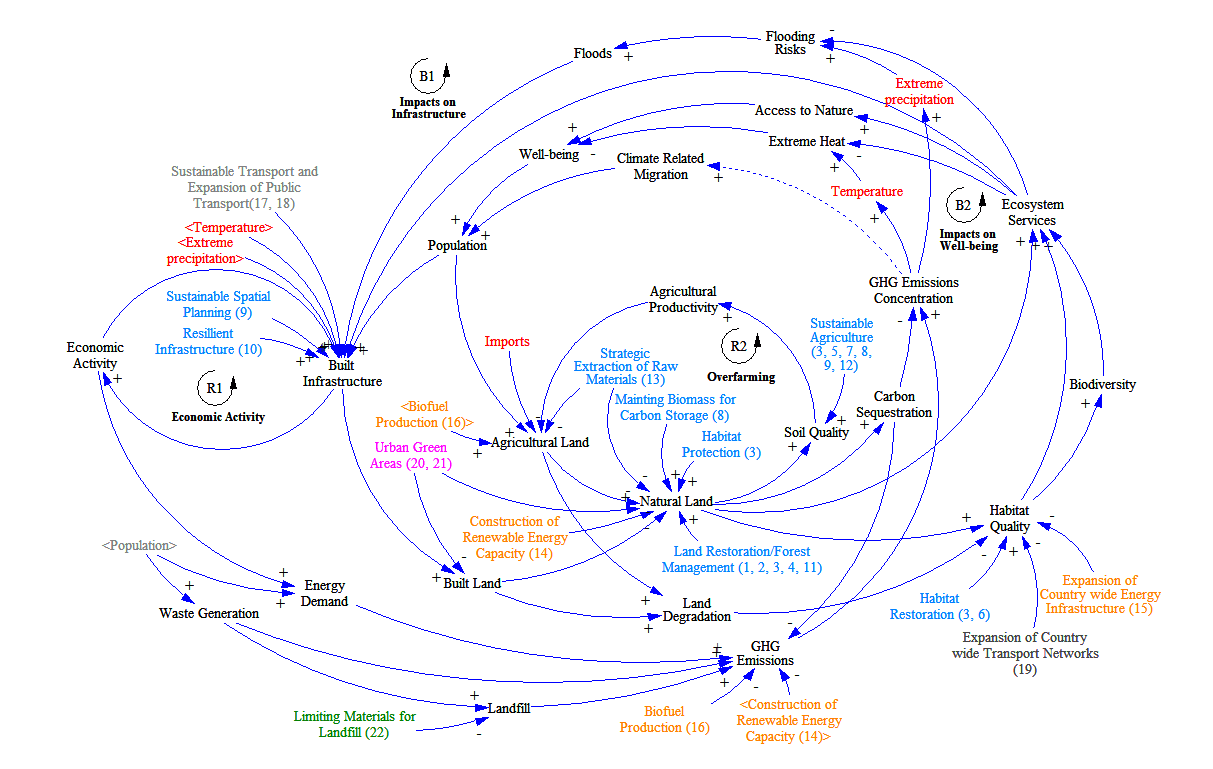

Figure 2. CLD for the European Union

The European Narrative

Historically, population growth has been the primary driver of land use change in Europe, fueling demand for housing and food, as well as accompanying infrastructure (R1 and R2). The increases in population and construction have stimulated further growth over time, resulting in higher consumption and the development of a diversified urban economy. On the other hand, this has also resulted in greater land requirements. With fewer green spaces and natural areas remaining, ecosystem services have declined, impacting various areas such as flood resilience. Over time, these changes have triggered economic impacts for infrastructure (B1), as well as undesirable social repercussions (B2). In summary, the historical drivers of land change have led to both positive economic and social outcomes, but also tradeoffs and side-effects, primarily due to negative environmental impacts.

Practice Case Narratives

Development expansion

These dynamics related to construction have also been observed in the assessments carried out for several Practice Cases, where urban development and/or agriculture expansion have resulted in lower climate resilience, as seen in recent events in central and eastern Europe. A notable example is the Mazovian Practice Case in Poland, where a large migration from rural to urban areas has triggered land conversion and, unfortunately, increased flood risks. This trend is unlikely to decline, as the growth of high-density urban areas are driving up land prices, resulting in further outmigration from rural areas.

Agriculture

Concerning food supply and agriculture land, a trend toward agriculture intensification has been observed. This intensification comes at the cost of sustainable land use and agricultural practices, leading to both high productivity and low soil quality (R2). Given known tradeoffs between production inputs and soil quality, land expansion for agriculture may be expected in the future. With more natural land potentially being converted for agriculture, ecosystem service provisioning may further decline and the need for built infrastructure will increase (B1), further depleting natural land.

This dynamic emerged in the case studies of South Moravia (Czechia) and Flanders (Belgium), where unsustainable agricultural practices exacerbate the loss of biodiversity and soil health. In South Moravia, agricultural production and environmental concerns are in direct conflict, while in Flanders, agricultural intensification is placing greater pressure on ecosystems. These situations underscore the urgent need for sustainable land management that strikes a balance between production and environmental conservation.

Climate Change

In relation to the drivers of climate change, both economic activity and population growth consume energy, generate waste, and utilise land for food and shelter, all of which contribute to global Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions. In addition to GHG emissions, energy use and waste result in air and water pollution, further impacting human wellbeing; in the EU almost 330,000 annual premature deaths can be attributed to air pollution. Nature provides valuable services such as carbon sequestration and the absorption of air pollutants; however, historical trends indicate that we are not heading in the right direction (see Figure 2).

Balancing Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability

Overall, we find that the relationship between economic growth and land demand requires a delicate and complex balancing act. As economies grow, the demand for land—whether for agriculture, infrastructure, or urban expansion—inevitably increases. This growth often comes at the expense of natural ecosystems, leading to the loss of biodiversity, reduction of carbon sinks, and increased environmental degradation (see Figure 2).

Top-down policies from the EU can help in preserving natural capital, with examples including the protection of habitats, promotion of sustainable agriculture, and support for land restoration. Linking back to the CLD in Figure 2, these strategies would limit the strength of R2, by boosting natural land which in turn would reduce negative impacts on population and infrastructure (B1 and B2).

However, these intervention options may result in side effects. In the Mazovian case, for example, the promotion of green spaces is expected to improve wellbeing by increasing access to nature, but it is also likely to increase land and housing prices, resulting in potential inequalities.

Navigating these complex dynamics requires thoughtful planning that takes into account the unique socio-economic and environmental contexts in which we live. While economic development is essential for improving livelihoods and advancing society, it must be balanced with strategies that protect natural landscapes and promote ecologically sustainable land-use practices, while also considering who benefits from these policies. Without this balance, short term economic gains may come at the cost of long-term environmental sustainability and the overall well-being of society.

Banner photo by Sam Jotham Sutharson on Unsplash