PLUS Change in Depth: Political Economies of land use change – Lessons from across Europe

In this article, we spotlight some of the insights from our recent work on political economies of land use decision-making in twelve European cases by investigating the relevant policies and actors.

Article by Simon Vaňo of CzechGlobe

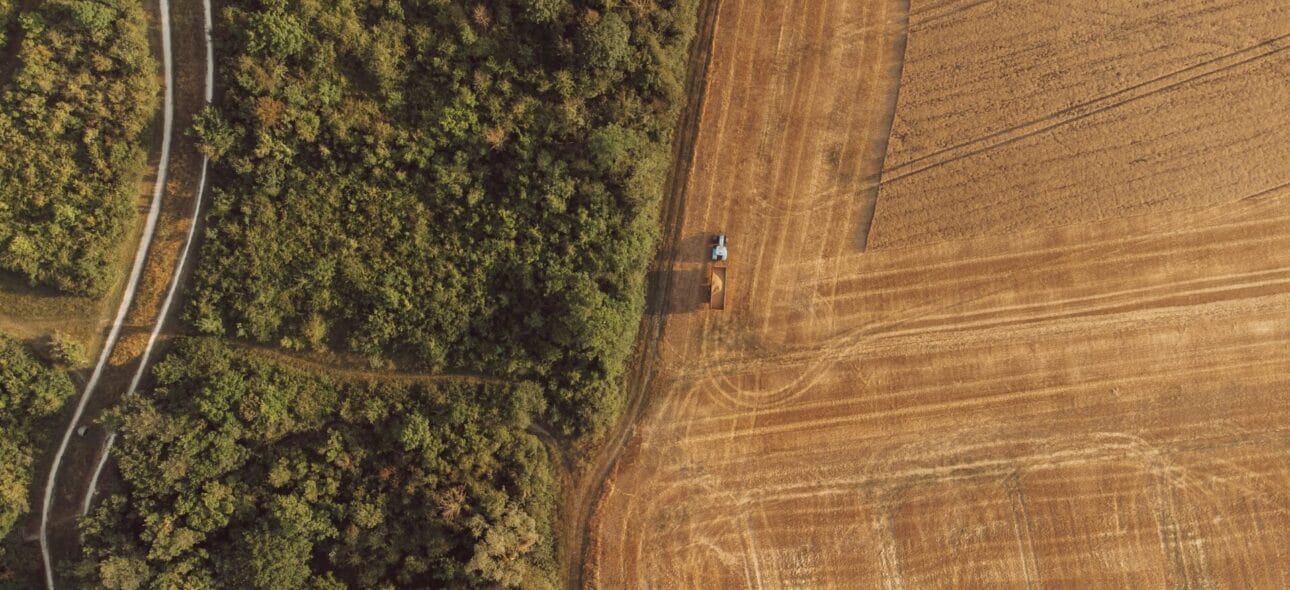

Whether it is farmland, forest, urban area, or wetland, the way we use and manage land is deeply rooted in and reflects social, political, and economic dynamics. The PLUS Change project has been working across twelve Practice Cases in Europe to unpack these dynamics, for instance, by exploring how different actors, governance and policies shape land use change. Here, we specifically focus on the role of different actors, the power relations, competing interests, institutional and policy settings that altogether constitute opportunities and constraints for building more sustainable and equitable landscapes.

Perhaps the main message is that actors involved in land-use decisions are diverse, but their influence is uneven. Local governments, such as those in the case of Nitra City in Slovakia, often play key roles in issuing binding regulations on zoning, housing, or spatial development. Yet in other cases, like the Kaigu Peatland in Latvia, national authorities dominate decision-making, leaving local governments with little say. Local governments, while central to implementation, are generally often pressured by conflicting policy demands from higher levels and by competing interests on the ground. Regional governments, such as those in Flanders or Île-de-France regions, also hold substantial power, particularly in strategic planning and cross-municipal coordination. Alongside these formal institutions, other actors such as NGOs, planning agencies, farmers, NGOs or citizens are present but often have limited power to shape decisions. NGOs and research institutions bring expertise but remain peripheral to formal processes. Citizens are consulted but rarely in the same position as decision-makers. This also suggests that equity concerns, in terms of who gains and who loses from particular land-use decisions, are not systematically addressed.

These dynamics are not only coming from institutional settings but also social and economic conditions. As an example, large landowners and private investors, though underrepresented in the workshops conducted within PLUS Change project, exert disproportionately higher influence than other actor groups. In South Moravia, Czechia for instance, agricultural and energy businesses shape land-use outcomes through investment choices and lobbying. Conversely, small landowners, associations, and citizens often lack decision-making power, even though they are directly affected by changes in land use. Natural resource managers, such as forestry managers in Province of Lucca, or water managers in a cross-border case of Three Countries Park, may play critical roles in policy implementation but are seldom included in strategic decision-making processes.

Policies are complex too, weaving together layers of local, regional, national, and EU-level instruments. In the case of Zaanstreek-Waterland, the Netherlands, long-term climate neutrality goals guide urban planning, yet these interact with national housing targets and EU emissions directives, sometimes creating tensions between growth and sustainability. In Surrey, UK, policies emphasise economic development and housing, but local actors must reconcile these with ambitious national climate targets. In contrast, policies in the Green Karst region in Slovenia focus heavily on rural development, cultural heritage and agriculture, often limiting nature conservation objectives. Additionally, across the cases, binding regulations and monitoring mechanisms are often weak, limiting the potential of strategic policies and creating a so-called “implementation gap”.

Different policies may create tensions across different actor groups. Citizens and NGOs often benefit from conservation funding and improved environmental conditions, as seen in the cases of Zaanstreek-Waterland and Three Countries Park, but they can also face unintended consequences such as rising housing prices or displacement, as reported in Nitra City and Mazovia Region, Poland. Similarly, businesses may profit from development-oriented policies, such as investment-friendly frameworks in Surrey, but face restrictive regulations in places like Île-de-France or Green Karst. Natural resource managers benefit from conservation incentives in some cases, yet in the case of Kaigu peatland, strict protections limit their use of land.

What emerged from this analysis is a picture of land-use governance that is deeply shaped by power asymmetries, top-down governance, and limited collaboration across actors and sectors. Analysis of the interplay between actors and policies highlights that we need to rethink how we govern land and how we navigate land use conflicts in order to work toward just, inclusive and sustainable land use strategies. While no single blueprint exists, learning from diverse contexts helps us identify common challenges and potential pathways forward, which will be in focus in an upcoming blog post!

Learn more in Deliverable 4.1, Intervention points for creating land use policy and decision-making change!